Frank Herbert first published his science-fiction epic Dune back in 1965, though its origins lay in a chance encounter eight years previously when as a journalist he was tasked to report on a dune stabilisation programme in the US state of Oregon. Ultimately, this set the wheels in motion for the recent film adaptation.

The large and inhospitable sand dunes of the desert planet Arrakis are, of course, very prominent in both the books and film, not least because of the terrifying gigantic sandworms that hunt any movement on the surface. But just how high would sand dunes be on a realistic version of this world?

Before the movie was released, we took a scientific climate model and used it to simulate the climate of Arrakis. We now want to use insights from this same model to focus on the dunes themselves.

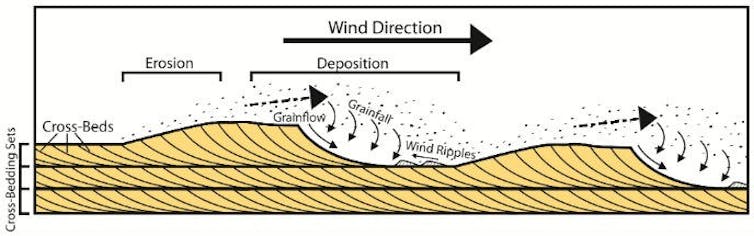

Sand dunes are the product of thousands or even tens of thousands of years of erosion of the underlying or surrounding geology. On a simple level, they are formed by sand being blown along the path of the prevailing wind until it meets an obstruction, at which point the sand will settle in front of it.

There is certainly no shortage of wind on Arrakis. Our simulation showed that wind would routinely exceed the minimum speed required to blow sand grains into the air, and there are even some regions where speeds regularly reach 162 km/h during the year. That’s well over hurricane force.

Sand dunes in the book are said to be on average around 100 metres high. However, this isn’t based on actual science, more likely it’s what Herbert knew from his time in Oregon as well as the world we live in. But we can use our climate model to predict what the general (and maximum) attainable height might suggest.

Where the wind blows

The size and distance between giant dunes are determined not simply by the type of sand or underlying rock, but by the lowest 2km or so of the atmosphere that interacts with the land surface. This level, also known as the planetary boundary layer, is where most of the weather we can see occurs. Above this, a thin “inversion layer” separates the weather below from the more stable higher-altitude part of the atmosphere.

The growth of sand dunes and theoretical height is determined by the depth of this boundary layer where the wind blows. Sand dunes stabilise above the wind at the altitude of the inversion layer. The height of the boundary layer – usually somewhere between 100 metres to 2,000 metres – can vary through the night as well as the year. When it is cooler, it is shallower. When there is a strong wind or lots of rising warm air, it is deeper.

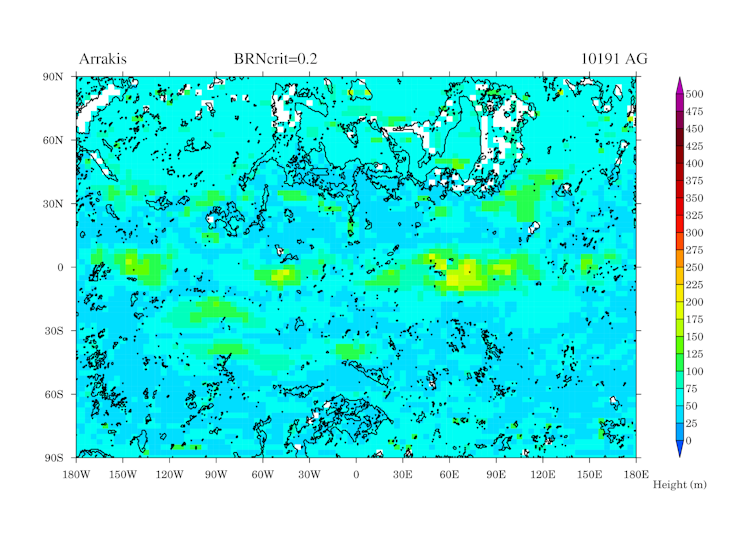

Arrakis would be much hotter than Earth, which means more rising air and a boundary layer two to three times as high over land compared with ours. Our climate model simulation, therefore, predicts dunes on Arrakis would be as high as 250m, particularly in the tropics and mid-latitudes. That’s about three times the height of the Big Ben clock tower in London. Most regions would have a more modest average height of between 25m and 75m. As the boundary layer is generally higher everywhere on Arrakis the average dune height is in general twice that of Earths.

We were also able to simulate the space between dunes, which can also be determined by the height of the boundary layer. Spacing is highest in the tropics, a little over 2km between the crest of one giant sand dune to the next. However, in general, sand dunes have a spacing of around 0.5 to 1km crest to crest. Still plenty of room for a sandworm to wiggle through. Scientists looking at Saturn’s moon Titan have run this same process in reverse, using the space between dunes – easy to measure with satellite images – to estimate a boundary layer of up to 3km.

As nothing can grow on Arrakis to stabilise these sand dunes they will always be in a state of constant drift across the planet. Some large dunes on Earth can move about 5m a year. Smaller dunes can move even faster – about 20m a year.

Mountain-sized dunes?

Our simulation can only give the general height that most sand dunes would reach, and there would be exceptions to the rule. For instance, the largest known sand dune on Earth today is the Duna Federico Kirbus in Argentina, a staggering 1,234m in height. Its size shows that local factors, such as vegetation, surrounding hills or the type of local sand, can play an important role.

Given Arrakis is hotter than Earth, has a higher boundary layer and has more sand and stronger winds, it’s possible a truly mammoth dune the size of a small mountain may form somewhere – it’s just impossible for a climate model to say exactly where.

Scientists have recently revealed that as the world warms the planetary boundary layer is increasing by around 53 metres a decade. So we may well see even bigger record-breaking sand dunes as the lower atmosphere continues to warm – even if Earth will not end up like Arrakis.![]()

-----------------------------

This blog is written by Caboteers Dr Alex Farnsworth, Senior Research Associate in Meteorology, University of Bristol and Dr Sebastian Steinig, Research Associate in Paleoclimate Modelling, University of Bristol and Dr Michael Farnsworth, Research Lead Future Electrical Machines Manufacturing Hub, University of Sheffield,

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.