“Plants, whether they are enormous, or microscopic, are the basis of all life including ourselves.” This was David Attenborough’s introduction to The Green Planet, the latest BBC natural history series.

Over the last 500 million years, plants have become interwoven into every aspect of our lives. Plants support all other life on Earth today. They provide the oxygen people breathe, as well as cleaning the air and cooling the Earth’s temperature. But without water, plants would not survive. Originally found in aquatic environments, there are estimated to be around 500,000 land plant species that emerged from a single ancestor that floated through the water.

In our recent paper, published in New Phytologist, we investigate, at the genetic level, how plants have learnt to use and manipulate water – from the first tiny moss-like plants to live on land in the Cambrian period (around 500 million years ago) through to the giant trees forming complex forest ecosystems of today.

How plants evolved

By comparing more than 500 genomes (an organism’s DNA), our results show that different parts of plant anatomies involved in the transport of water – pores (stomata), vascular tissue, roots – were linked to different methods of gene evolution. This is important because it tells us how and why plants have evolved at distinct moments in their history.

Plants’ relationship with water has changed dramatically over the last 500 million years. Ancestors of land plants had a very limited ability to regulate water but descendants of land plants have adapted to live in drier environments. When plants first colonised land, they needed a new way to access nutrients and water without being immersed in it. The next challenge was to increase in size and stature. Eventually, plants evolved to live in arid environments such as deserts. The evolution of these genes was crucial for enabling plants to survive, but how did they help plants first adapt and then thrive on land?

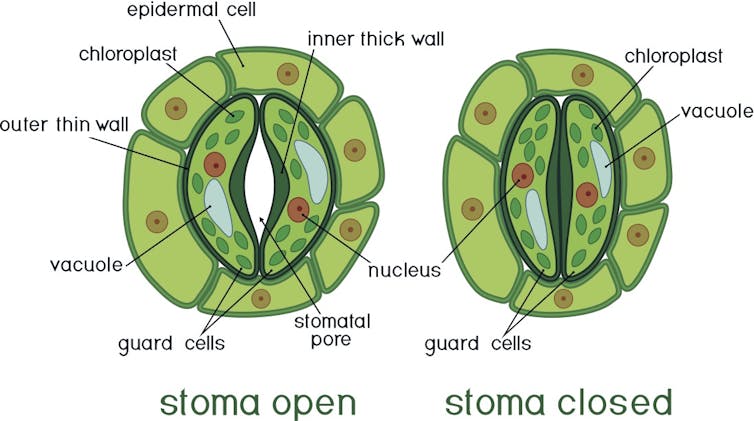

Stomata, the minute pores in the surface of leaves and stems, open to allow the uptake of carbon dioxide and close to minimise water loss. Our study found that the genes involved in the development of stomata were in the first land plants. This indicates that the first land plants had the genetic tools to build stomata, a key adaptation for life on land.

The speed in which stomata respond varies between species. For example, the stomata of a daisy close more quickly than those of a fern. Our study suggests that the stomata of the first land plants did close but this ability speeded up over time thanks to gene duplication as species reproduced. Gene duplication leads to two copies of a gene, allowing one of these to carry out its original function and the other to evolve a new function. With these new genes, the stomata of plants that grow from seeds (rather reproducing via spores) were able to close and open faster, enabling them to be more adaptable to environmental conditions.

Old genes and new tricks

Vascular tissue is a plant’s plumbing system, enabling it to transport water internally and grow in size and stature. If you have ever seen the rings of a chopped tree, this is the remnants of the growth of vascular tissue.

We found that rather than evolving by new genes, vascular tissue emerged through a process of genetic tinkering. Here, old genes were repurposed to gain new functions. This shows that evolution does not always occur with new genes but that old genes can learn new tricks.

Before the move to land, plants were found in freshwater and marine habitats, such as the algal group Spirogyra. They floated and absorbed the water around them. The evolution of roots enabled plants to access water from deeper in the soil as well as providing anchorage. We found that a few key new genes emerged in the ancestor of plants that live on land and plants with seeds, corresponding to the development of root hairs and roots. This shows the importance of a complex rooting system, allowing ancient plants to access previously unavailable water.

The development of these features at every major step in the history of plants highlights the importance of water as a driver of plant evolution. Our analyses shed new light on the genetic basis of the greening of the planet, highlighting the different methods of gene evolution in the diversification of the plant kingdom.

Planting for the future

As well as helping us make sense of the past, this work is important for the future. By understanding how plants have evolved, we can begin to understand the limiting factors for their growth. If researchers can identify the function of these key genes, they can begin to improve water use and drought resilience in crop species. This has particular importance for food security.

Plants may also hold the key to solving some of the most pressing questions facing humanity, such as reducing our reliance on chemical fertilisers, improving the sustainability of our food and reducing our greenhouse gas emissions.

By identifying the mechanisms controlling plant growth, researchers can begin to develop more resilient, efficient crop species. These crops would require less space, water and nutrients and would be more sustainable and reliable. With nature in decline, it is vital to find ways to live more harmoniously in our green planet.![]()

----------------------

This blog has been written by Alexander Bowles, research associate, University of Bristol.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Alexander Bowles |